PARAGUAY: LIFE OF A SOY FARMER IN CANINDEYÚ

The department of Canindeyú, Paraguay, is a mysterious place. On the one hand, it has an infamous reputation as the hotspot for drug trafficking and illegal merchandise in whole South America, on the other it seems like the most peaceful place on earth. Due to my prior, rather speedy research on the security of Paraguay (which I usually treat with doubt anyways), I wasn’t supposed to end up here. However, following local (and by this, I don’t mean just Paraguayans, but Paraguayans living in Canindeyú) advices, this is exactly where I cycled. And in the aftermath, I’m more than glad I did.

Canindeyú: promised land of drug trafficking and agriculture

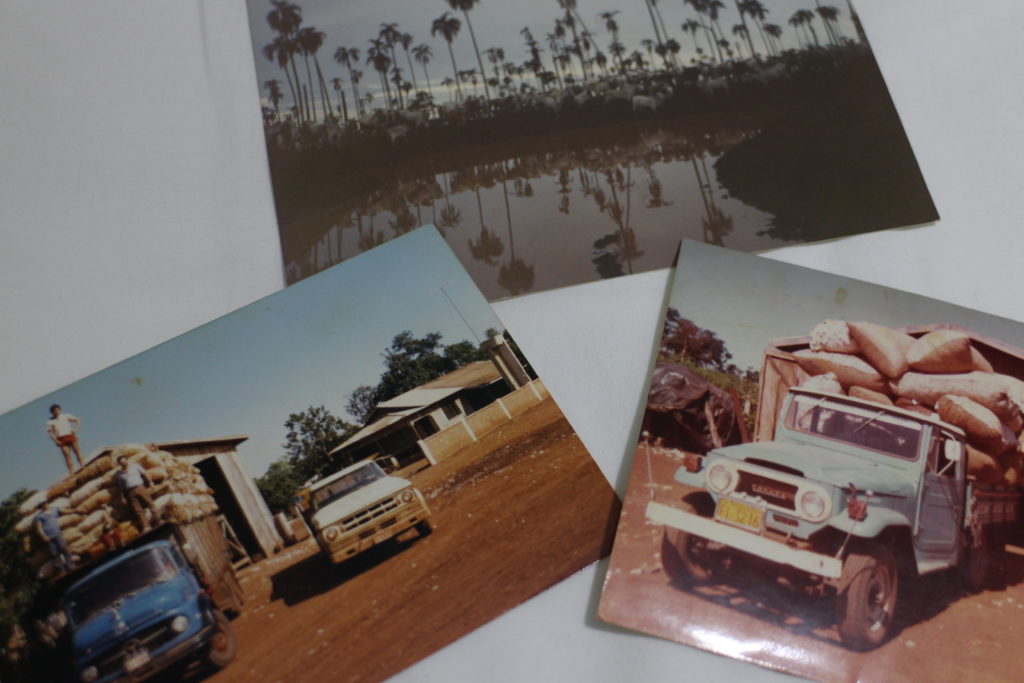

Paraguay has always been a country of transit between Brazil and the rest of Latin America. Therefore, it is only logical that an area like Canindeyú, which lies right at the border of Brazil, is effected by this transit. In fact, a notable part of Canindeyú’s income has, according to unofficial statistics, for years been drug trafficking and the cultivation of marihuana. When reading this, you think the place must be straight out of NYPD Blue, yet to a cyclist, a random passerby or even a local soy farmer, it’s nearly impossible to see traces of this reality. The only thing that points out to illegalities in the area is the numerous amount of police patrols that love playing it tough on cars with Brazilian license plates, yet wave happily at a cyclist. And among the endless fields of soy, corn, manioc and sugar cane, it is natural to see trucks lined up in cues, loaded with their cargo.

According to official statistics, the largest income of Canindeyú is agriculture. This is also where a vast amount of the production of my beloved protein income, soy, takes place. In fact, at the moment Paraguay is the 6th biggest producer of soy beans in the world, and the country itself estimates that by 2025 it will be third. Back home, I consume soy products almost daily, so imagine how fascinating it has been for me to see, how them little soy beans are grown. As I am no agronomist, I’ll just go gonzo and tell about a local farmer instead of the actual cultivation process.

A disclaimer: this post is not about deforestation, landownership, Monsanto or worker’s rights in Paraguay. It’s about a farmer whose life I got to know through countless questions, tireless observation and amazing hospitality.

Afonso Pires: a soy farmer in Canindeyú

The essence of the life of a soy farmer is simple: soy. Out of corn, wheat, oat and soy, the latter is the one that sells best, and therefore, the whole year of most farmers is based on the growth of soy. Although corn and wheat can sometimes bring a notable income to a farmer (depending on the amount of product on market), more often they are cultivated as means to make the ground more fertile and because continuous monoculture (the practice of growing only one crop in a field year after year) is not advised (because it increases the probability of pests and diseases). Yet, sometimes two seedings can be made on the same year, if the weather conditions are optimal. If they’re not = no soy = less money. My conclusion: it’s definitely way easier to be a cycling blogger.

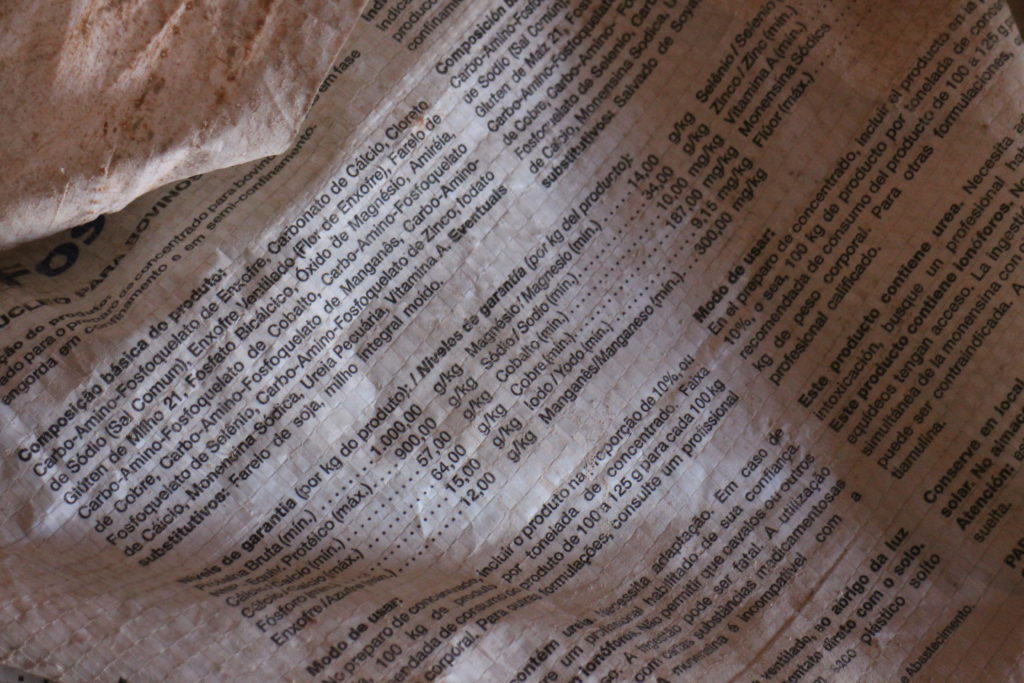

First of all, I have to say that soy is produced yet not eaten in Paraguay. There is no tofu anywhere and although ‘soy meat’ exists, it is definitely not wide spread. Soy is mainly exported (also as processed brans and oil), mostly to China. Regarding this, Afonso showed me two applications: one called Marine Traffic, which shows in real time all the ships crossing the waters of the world and the cargo (supposedly) in them and another for checking the change in the price of soy in real time. Most of the soy used internally in Paraguay is the one used for feeding cattle, pork and chicken. Which, as a matter of fact, is a huge amount of the produced product. In addition to this, the soy oil resulting from industrial processing, is re-used in agriculture and in Paraguayan internal industries. Soy is also

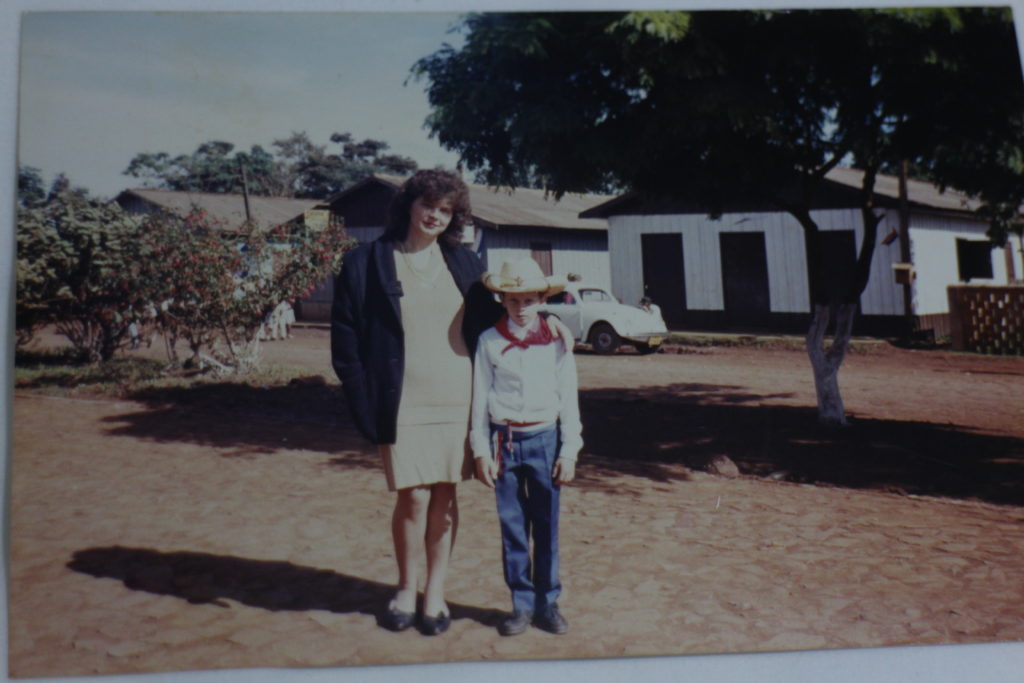

Afonso Pires is one of the two soy farmers I stayed with in Canindeyú. Decades ago, his Brazilian parents bought a piece of land in Paraguay, and nowadays Afonso, his brother Sergio and their father Sergio (yep, it’s not a typo) work that land (which has, since then expanded and keeps on expanding). As a matter of fact, most of the big soy production in Paraguay belongs to people of Brazilian descent. Paraguayn land has for decades been popular among Brazilians, not only because of fertility, but because of its price. And it has obviously been a good business, as the landowners of Canindeyú seem to live very well in Paraguay. They have beautiful, large houses and the newest gear for cultivation.

Me and Afonso visited the fields of Afonso’s family so I could see first hand where it is that the magic happens. The seeding of soy only started one day after my leaving Katueté, which means that during my stay the farmers of the area were anxiously waiting for the rain to stop and the land to dry out. The process of soy production is an art, and as I am not the agronomist Afonso is, I won’t even try to explain the details. However, what I will share is a couple of things I learned which look at the hysteria concerning transgenic soy in Finland.

Afonso: “the controversy on transgenic soy is due to lack of knowledge”

In Finland, there is a continuous debate about what transgenic soy does to human health. Many have probably heard about the philosophy of Monsanto, which is exactly the one that Afonso applies in his cultivation. As I honestly don’t know much about plants, I asked Afonso to explain to me (and you) his viewpoint on this:

“Transgenics are organisms which have been genetically modified by agronomic engineers. Why? Mainly for increasing the productivity of crops. There are various transgenics on the market. For example: Soja RR, which is resistant to Roundup Ready, a herbicide that control weeds growing in the midst of crops. Maiz Bt, which is resistant to insects that eat the leaves and the sprigs of corn. Draught resistant soy, which can grow with small amounts of water especially in places with less rain.

The controversy about transgenics is that many people don’t know how they function, which is why it is said that it can be harmful to health. However, people exaggerate the amount of agrochemicals used in transgenics. In fact, the use of agrochemcals is much more widely used in conventional plants than in transgenics, as it is much easier to cultivate organic transgenics than organic conventional plants.

The way transgenics are produced is through scientific research. Scientists study the genes of plants to check, for example, which part of their DNA makes them resistant to insects. Before these genetic studies, people used to use insecticides to control the cultivation. Nowadays, soy has, for example, been genetically manipulated agains worms, so that the use of insecticides has decreased significantly”.

This is precisely why I love being with people who come from a totally different reality than my own. Instead of blindly trusting the media, I get to meet these people and ask them personally about their opinion and explanation. Of course, the genetic manipulation is not the only controversy concerning soy production, but I am fascinated about now having friends who can give me their viewpoints on a discussion, which is very interesting and very close to my everyday life as a vegetarian.

Strangerless sidetracked: a story about Afonso’s mother

Maria de Fe (formerly Almeida) Pires was officially born in the year 1955, in Brazil, to Brazilian parents. As land was cheaper in Paraguay already back then, Maria’s family decided to move there for better business when Maria was 13-years-old. Soon after, Maria started working at a mercería (a goods shop) before meeting her future husband who she started going out with (however, as according to tradition, never without a chaperone). After dating the boy for some time, Maria’s father decided it was time for the daughter to marry. As the legal age for marriage at the time was 15, he cleverly falsified his daughter’s documents and changed the date of her birth. Waiting one more year wasn’t an option (mind you, it was the duty of a father to see to it, that his daughter stayed a virgin until marriage. If this wasn’t the case and it was discovered after the vows, a man had the right to return the newly wedded wife back to the family.) After the wedding, the newly wedded couple moved to a house in Paraguay and lived on on cattle business before extending also into soy.

How I met Afonso?

I met Afonso through Maiara, a couchsurfing host whose family kept my bicycle in Brazil while I was taking a break from cycling. Maiara told me about her friend, Afonso, who lives in Katueté and was willing to host me. Before even getting to Katueté, Afonso hooked me up with his family, living in Guaíra. So, the last place I stayed at before crossing over to Paraguay, was at Afonso’s parents’. In Katueté, I met Afonso’s friend Alessandra. After leaving Katueté, my next stop was a small town named El Naranjito, where Alessandra’s dad hosted me. From there, I headed to Curuguaty, where I again stayed with a friend of Afonso’s, Marilde and her family. From there I cycled to a small town named San Estanislão (or Santaní, as locals call it) where I stayed with Marilde’s boyfriend’s cousin, Gladys. So, Maiara and Afonso and the whole lot covered pretty much whole Paraguay for me concerning accommodation and company! I’m now already in Asunción, so I don’t think I’ll be seeing much of my tent before crossing over to Argentina again.

Este tema es complejo. Sin duda este es un aspecto. Pero no olvides que hay otros. Porque este tema de la soja transgénica en Paraguay, está ligado con deforestación, expulsión de campesinos, desprecio de la cultura y tecnología local de cultivo campesino familiar, empobrecimiento biológico porque un cultivo transgénico elimina toda la variedad de vida, modalidad de explotación agraria con bajísima mano de obra, etc. No te vayas del país creyendo que todo es tan simple.

Hola Julio! Por eso puse el disclaimer. Lo tengo claro que es un tema complejo. En mi blog lo que quiero hacer es presentar las realidades de las personas que voy conociendo, aunque claramente la realidad de cualquier persona es solo un lado de la realidad objetiva (existe una realidad objetiva?). Lo que sí para mi es interesante es contar lo que veo y dejar a los demás de hacer los conclusiones. No quiero entrar en discusiones políticas. Porque? Porque lo que me encanta en el hecho de estar viajando es que puedo observar todo bastante fácilmente sin prejuicios (sin lentes de cualquier tipo) que muchas veces son creídos por los medios (y no a través de contactos personales con las cosas). Una cosa que ya a veces me resulta difícil en Finlandia. A mi me encanta que voy conociendo gente de cada estrato social en cada país donde esté, y voy conociendo lo que ellos todos piensan (he hablado también con gente que trabaja en el campo, me paré muchas veces a tomar el tereré y hablar con ellos mientras estaba pedaleando. Me encantaría escribir sobre muchas otras cosas, pero tengo un falta crónica del tiempo :D!). No quiero hablar sin saber, y por eso me quiero limitar solo a experiencias personales.